"A few hours’ mountain climbing turns a rogue and a saint into two roughly equal creatures."

-- Friedrich Nietzsche, The Wanderer and His Shadow

-- Friedrich Nietzsche, The Wanderer and His Shadow

Australia is the oldest, driest, and flattest continent on the planet. Most Australians know next to nothing about mountains and mountain-climbing, having never seen them before, and most Western Australians know even less. For those of us who grew up in Perth, our idea of a mountain range is an escarpment known locally as the “Darling Range”, rising as much as 300 metres above sea level in some places, a greenish blur on the eastern horizon. Our idea of mountaineering involves hauling a full esky over a sand dune or across a sloping lawn. So it’s fair to say that since we learned of our acceptance into the JET programme last year, Emma and I had our hearts set on climbing a real mountain, the biggest in Japan. And therefore our journey to the summit of Mt Fuji really began in Whitford City Shopping Centre (of all places) in the weeks prior to our departure from Australia, where we acquired cold-weather gear and, more importantly, decent hiking shoes. The intervening year has been spent in anticipation of the day when those shoes, already road-tested in places such as Mt Rokko, Mt Shosha, Sumaura, and the mountains of Wakayama, would tread the slow trail to the top of Japan’s most iconic landmark.

Of course, kudos must go to Emma and her go-between Shibata-sensei, without whose careful planning--including an extensive array of Google Map printouts spread out across our living room floor the previous weekend--this trip would not have been possible.

Day 1: Kawaguchiko

The bulk of our party converged at the bus station in Mishima: Emma and me, Shibata-sensei, Amanda, Suzie, Aimee, Dan C, Dan K, Louis, Chris Molina, Steven, Wendy, Case, Sean, Goran and Kin. (Dan K’s friend John, after what sounded like some arm-twisting, joined us later in the evening.) We were taken from Mishima to Gotenba by the angriest bus driver in Japan: he yelled at us gaijin for frivolous bell-pressing (when the actual culprit was an elderly local who had moved too slowly to reach the door before the bus pulled away from her stop), and his mood was not improved by two idiot motorists who were desperate to learn the meaning of “give way to the right” the hard way. Eventually, and hungrily, we reached the mountain lake resort of Kawaguchiko, and after a brief trip around the lake we found our lodgings for the night: a kind of Japanese bed-and-breakfast without the breakfast.

There amidst the mountains we did the Australian thing and enjoyed a barbecue, and watched the sun set over fields of blueberries. (Sucks to be you, doesn’t it?)

The ascent: Fujiyoshida to the 7th station

We’d planned an early departure on Sunday morning, but as there were no buses running at that time we bribed the proprietor of the B&B to drive us all to Kawaguchiko station, from where we made our way to Fujiyoshida at the base of the mountain. (We also parted ways with Shibata-sensei, who had decided not to climb the mountain.) It was at this point that about 5 members of our party decided to take the bus to the 5th station and climb from there; the rest of us started walking. I remember, looking ahead at the mountain, faint but looming, two thoughts occurring to me: (a) “We’ll be at the top of that by sunrise tomorrow,” and (b) “How the hell are we going to get there?” (The "Mount Doom" chapter from The Lord of the Rings also entered my mind.)

Much of the climb from the base to the 6th station was spent in cool and pleasant forest. There were a few surreal moments—-coming suddenly out of the bushland upon a noisy expressway, watching a team of rollerbladers skate up the hill, and being overtaken by joggers. At a place called Umageshi, a name which means horses can go no further, though that would fail to account for the horse droppings we found later on beyond the 6th station, some kindly old ladies beckoned us to their hut to enjoy some free o-den, and to have our water bottles filled. (I guess they were volunteers of some sort.) In the vicinity of the 5th station, which we somehow managed to bypass, a thick fog descended upon the trail, and we knew we had reached the clouds. After a late lunch at the 6th station, where Emma and I bought climbing sticks (a.k.a. "Fuji sticks," which can be branded at each station and kept as a souvenir of the climb), we passed beyond the clouds and, for the first time, caught a clear glimpse of the peak, shining red in the afternoon sun.

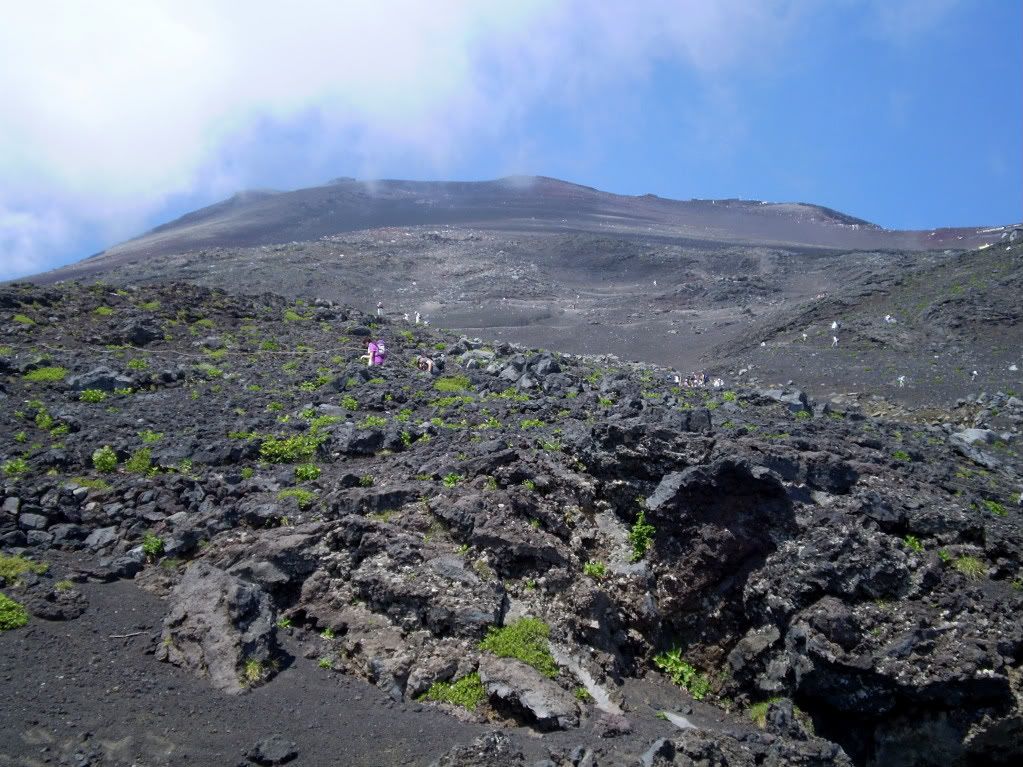

At this point the woods were beginning to thin out. They finally disappeared at a bus station, probably 2 to 2.5 kilometres above sea level, where climbers were disembarking coaches from a route known as the Subaru Line. They were the first sizeable numbers of people we had seen since Kawaguchiko. We had reached the desolate upper slopes of Mt Fuji, rising from an ocean of cloud. Ahead, the path climbed the face of the mountain in sharp zig-zags, and beyond that, we could see the series of huts, one seemingly on top of the other, that comprised Stations 7, 8, and 8.5. Closer to the 7th station, where we would be staying for the night, we had to do some actual climbing, which is not a simple proposition when you’re hauling an 8kg backpack. (It was even less simple when we had to do it again in the dead of night.) At 6pm, we dragged our aching and protesting muscles into our hut, where a cool 7500 yen apiece got us a TV dinner, a bento for the road, and a comfortable few hours sleep inside a small cupboard lined with futons. It was remarkable to observe how much we had all bonded throughout the day. There we were, soaked from head to foot in a day’s worth of road grime and sweat, and well inside each others’ personal spaces, and nobody seemed to mind. Some of us weren't even ashamed to get semi-naked in front of our comrades in order to wet-towel ourselves clean and change into warmer clothes for the final stage of the climb; though Goran was gentlemanly enough to provide a makeshift dressing room for Kin with his quilt.

The final stage: 7th station to the summit

Whether it was the anticipation of a gruelling climb and a breathtaking sunrise as a reward, or the noisy departure of another party of climbers at 930pm, it is doubtful that any of us got more than an hour and a half’s sleep. We left the hut at 1130pm on Sunday night, and immediately proceeded to scale the steep mountain face. In the dark. My headlight, purchased for the princely sum of 100 yen, was precariously clipped to the brim of my visor. I was half asleep, and I kept knocking the light to the ground with my Fuji stick, whereupon it would break open and the batteries would fly out. I was a more than a little panicked at this stage, and needed every ounce of Emma’s moral support. Emma actually lost her headlight long before I discarded mine in disgust, but it didn’t faze her, seeing as the moon was full and there were dozens of other climbers around to light the way. I had collected my wits by the time we reached the first hut of the 8th station, and was a little more confident of not dying before sunrise. To tell you the truth, if there was any dying to be done on Mt. Fuji, it certainly wouldn’t be caused by falling off. The path was steep, and narrow, and we had to clamber over rock, but there were rope fences on either side to guide the way, and at certain points thick metal rods had been driven into the stone to assist us.

On the previous day we’d walked for ten hours, and it seemed like we’d covered ten hours’ worth of ground. Beyond the 7th station, the journey seemed interminable, and the summit seemed forever out of reach, like that neverending hallway in the movie Poltergeist. The 8th station alone went on forever, and the higher we climbed, the more climbers poured out of the huts to join our route. By this stage we’d passed Aimee, Steve, Wendy, Amanda and Suzie, and the others had raced on ahead. Somewhere along the way Emma started hallucinating—-she began to think that the headlights worn by other climbers were pretty little birds—-so we stopped and ate the bento. We were still hopeful of reaching the summit by sunrise at 4.40 am; Emma checked the map at one of the huts and estimated that we would get there at 3.50. But we began to notice how crowded the path was becoming, and when Emma pointed out a tinge of golden light spreading across the eastern sky, things were looking ominous.

Well, we saw the sunrise, but not at the summit. After the 8th station came the "Real 8th station" (all the other 8th stations were just imitating), and then the 8.5 station and the 9th station, by which point we might as well have been queueing for a ride at Tokyo Disney. It didn't make a lot of difference, anyway: the sun rising over a foam of cloud looked just as magical a few turns above the 9th station as it would have done at the summit, which we eventually reached at 5.15am. Two members of our group had already had their fill of the mountain and departed by the time we arrived, and another two had to leave early due to work commitments. The others waited for the remaining climbers to reach the summit, among which included poor Amanda, who had twisted her knee at the 7th station and still managed to complete the climb. As we were on a tight schedule, we didn't have a chance to walk the whole way around the crater; I explored the northern and eastern face while Emma rested. At 7.30, it was time to descend.

Falling down the mountain, end up kissing dirt . . .

Our map indicated that the journey down the mountain, along the Subashiri route, would take no longer than a couple of hours. Sweet. We'd have time to shop for souvenirs at the 5th station, catch a bus to Lake Yamanaka, and hit the nearest onsen. Too easy.

The map was lying.

I can sum up the Subashiri descending route in one word: Mordor. Try this on for size: we had to half-walk, half-slide down a trail of loose rock and ash (technically known as "scree"), in blazing sunshine, for six hours. It was a good thing Emma and I were wearing the surgical masks that are popular over here, because dust was getting into every orifice that wasn't covered. I must have fallen over about four times--once into a nice drift of mud that had earlier in the day been melting snow. One stretch of the track could best be described as a two-kilometre landslide. The overpriced drinks at the 6th station added insult to injury. And spare a thought for Amanda, who had to negotiate all that with a knee injury. She was assisted for most of the way and put on a brave face, but the experience can't have been pleasant. When we finally reached the 5th station, we barely had time to board the bus to Gotenba. No souvenirs, I'm afraid, unless you count the most severe case of sunburn I've ever had in my life, which to this day has me molting like a cicada, but we'd all had quite enough of the mountain by then.

Oh, and the cyborg Goran, who waited around behind us on the summit until he could find Kin, caught up with us about half an hour down, and proceeded to jog the rest of the way (with Kin in tow). How does he do it?

Would we do it again? Yes, I think, as long as time and money allows. But we did come to Japan with the aim (or hope) of scaling Fuji at least once, and now we've achieved that. And there are a lot of other places in this country we would like to explore. We are glad, at any rate, that we have such memories to bring back with us to Australia, and that we were able to share this experience with good friends.